Category Archives for Uncategorized

The Importance of Thick Paint

When we think of contrasts in painting what comes to mind is dark and light value contrast, or cool and warm color temperature contrast, or the contrast of hard and soft edges.

A real important contrast is thick and thin paint. The thickness of the paint, when we apply it to the canvas, goes a long way to suggest form and depth as well as enhance sunlight and shadow contrast.

When we mix a color for a sunlit area the value and the color temperature is really impacted when we use thicker paint. I can mix a color for a light area and if it’s not thick enough it won’t have the impact of sunlight, even if I mix the right temperature and value. Thicker paint stands out more and looks lighter than thin paint.

As a learning tool, thick paint forces you to simplify (it’s hard to get too detailed with a brush full of paint), and helps to understand color better. It’s easier to understand the impact of a color with thicker paint.

Just like watercolor is designed for transparent washes, oil paint is designed for thick opaque brush strokes.

The painting below is a detail from a painting from the Teton Mountains. All the paint is thick but the light areas are thicker so they stand out from the darks. The thicker paint also makes the brushstrokes more important. I’m thinking about mass and value more than detail or trying to render objects.

This is a detail from a John Carlson painting. The darks seem to recede from the thicker lights. The stronger colors have more impact because of their thickness.

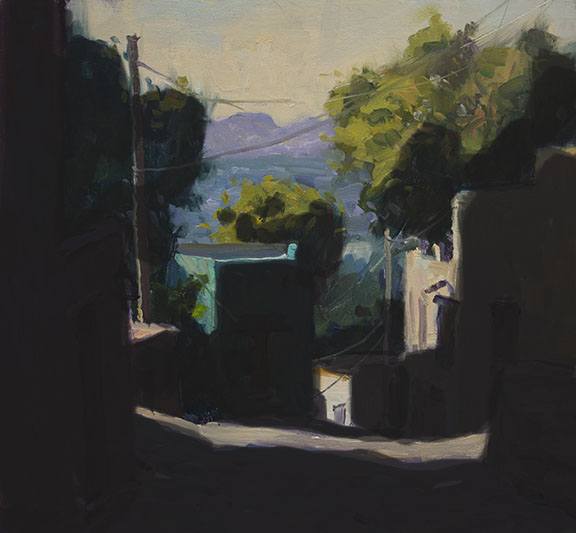

I painted this in southern Utah and used the thicker paint to show more form. The brushstrokes follow the shape of the trees and hills to accentuate their shape or direction. This also helps to keep things simple. When using photographs to paint from, it’s more effective to think in terms of the light brushstrokes following the form, it keeps me from being too literal with photos.

At first it can be hard to paint thick enough. Our tendency is to paint thin if we’re unsure, so use a palette knife or painting knife to mix your paint. It’s hard to mix thin paint with a palette knife.

Appreciating Winter Paintings

Since we are well into winter, I thought it would be a good idea to post some winter or snow paintings to appreciate.

Snow is interesting to paint because of the strong contrast of value, temperature and texture. Snow is wholly different from all the other landscape parts. It provides instant value contrast, it’s so white, it jumps off the canvas. It’s a different texture than branches, rocks or foliage, it can be as smooth as glass.

The color of snow depends on the type of light that hits it, and reflected light that’s bouncing around in the shadows.

It looks easy to paint but the subtleties in the value and color make it hard to paint well.

This is a George Innes painting. He kept it simple as far as the detail and it has a strong temperature contrast between the warm, yellow orange sky and the cool violets in the snow. What detail there is seems to fade into the soft edges.

Here is a John Francis Murphy watercolor. He really doesn’t paint much snow in it but he suggests the snow with the value of the paper. It still feels like winter.

In this painting by Willard Metcalf you can see the strong design of the light and dark shapes and very subtle value changes in the flat snow. It has an abstract feel to it.

This is a painting by Walter Luant Palmer. Very subtle value changes that give the snow a lot of form, and a strong contrast between the warm water and cool snow and background. He gives the painting a lot of atmosphere by pushing the background cooler and making the edges softer.

This last one is a drawing by Issac Levitan. It looks like a tonalist painting, all the value relationships are there, it doesn’t need any paint.

Faces of Impressionism: A show at the Kimble Art Museum

The Kimble Art Museum, in Fort Worth, Texas, is having a show on a variety of portraits painted in France from 1850 to 1900. Here are a few of the pieces in the show.

Also a catalog is available.

Creating Interest with Broken Color

This is a short video on broken color, one of the many subjects I cover in my Online Mentoring Class. If your interested in learning more about the classes visit this link: http://www.philstarkestudio.com/onlinementoring/

Starting At the Center of Interest

When we start a landscape painting, one of the things we need to establish is depth so it helps to start, back to front, getting the value and color temperature differences to make planes and objects recede. But there are some paintings where depth isn’t part of the focus. Paintings where the center of interest is not just the main focus, but the only focus, no messing around with background or a secondary center of interest.

Everything is simplified so the one object is what the viewer looks at. Composing is very important in these vignettes because there isn’t much depth to pull the viewer in and move them around the canvas. So it’s important to spend time cropping and eliminating unwanted stuff.

In the painting by Robert Vonnoh, American impressionist, early 20th century, his focus is entirely the trees but he still composed the canvas so that it isn’t just a tree study but a composed painting.

Robert Vonnoh

Phil Starke

When we’re painting outside it helps to focus on a center of interest and barely suggest the rest of the composition. In this painting of some fallen trees, I zoomed in and spent 90% of the time on the trees. It helped me to keep things real simple by just focusing on the trees.

Phil Starke

This is another demonstration of focusing on the center of interest and eliminating detail on all other parts of the landscape. The tractor has the strongest color, the most contrast and the most detail. Everything else fades away.

Anatomy of a Tree

Trees are like the human figure, they have a particular anatomy to them. (Read John Carlson’s Guide to Landscape Painting chapter 9.) The trunk is the skeleton of the tree, it sets up the motion and movement. The trunk should always gradually taper so the wider the trunk, the taller the tree. Also, make the trunk and branches more angular when you paint them, don’t round them off, that tends to make the trunks and branches look like wet noodles. Angular brushstrokes look stronger, like they can hold up a lot of weight. Like most objects in painting, the trees have to look solid and 3-dimensional and are generally darker because they are an upright plane. Making trees too light gives them a feeling of floating, not heavy.

This is a painting by John Carlson, notice how angular the trunks and branches are. It makes the trees look stronger.

This is a painting by T C Steele, an early 20th Century painter. Agian, angular branches make the tree look solid.

I painted this tree in the spring and kept the values darker than the ground which helps the tree look more substantial.

Painting Evening Light

The color of the sunlight in the evening or late afternoon is different than the light during the day. It has a very warm, orange look to it that saturates everything. The shadows are longer and more of a blue and reddish violet. The morning light is a little cooler, midday light is muted and flat, but evening light is warm and orange. If I’m painting outside in the late afternoon I will pre-mix an orange with alizarin crimson and cadmium yellow light and use it in all the sunlit areas along with the local color. For example, a green tree in evening light will have orange added to it. The shadow areas will be affected with ultramarine blue and alizarin crimson along with the local color.

This is a painting by Hanson Puthuff and all the colors in the sunlight are effected by orange, even the purple mountains are effected with the orange light.

In this painting by Edgar Payne you can see the really saturated orange in the cliffs and green grass.

This is a painting I did in Tucson, I applied orange or yellow orange to all the local colors in the low sunlight.

California Art Club Gold Medal Show

This my entry for California Art Club’s Gold Medal Show. Its a 24×36 oil of Point Lobos in the morning light. The show is March 29 to April 19 2015 at the USC Fisher Museum of Art, Los Angles, CA.

Point Lobos 24×36 oil

The Importance of Controlling the Chroma in Your Painting

Here’s a video tutorial on how to use chroma in your painting.

Light and Color

“When you consider the light in your painting think of it as something separate from form and color, although light causes both.” John Carlson, chapter 5, Guide to Landscape Painting. Carlson, early 20th century landscape painter and author of John Carlson’s Guide to Landscape Painting, is saying that light is something other then local color.

If I’m painting a red barn on a sunlit day then I’m really painting the effects of sunlight on the barn. Sunlight is a warm color and shadows, on a sunlit day are a cool color. So, the red barn turns to a lighter reddish-orange in the sunlight and in the shadow it turns into a red-violet.

Reflections, 20×24, oil, by Phil Starke

The local color of the barn is red but we don’t really see it on a sunny day, instead we see the effects of the sunlight and shadow.

The only time we really see local color is on a cloudy day. Color is a lot richer when it’s cloudy. There isn’t any sunlight effecting the color and value. We tend to think of cloudy days as gray in color but they are actually more saturated. So when you’re mixing color, remember you’re mixing the effects of light.