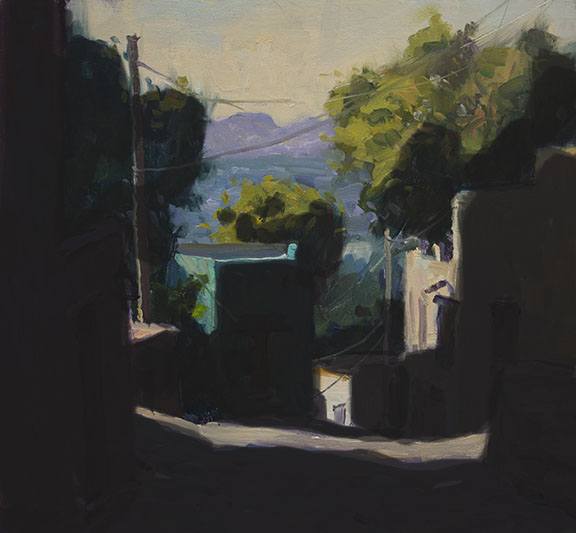

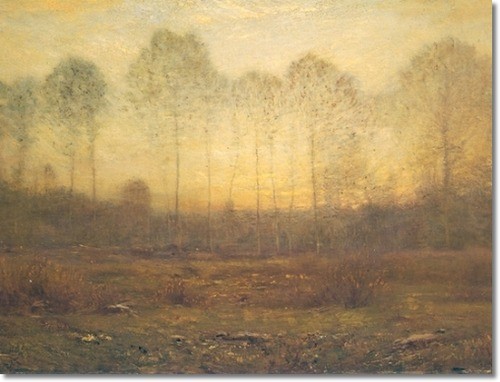

Oils are considered the best medium for learning how to paint because there are forgiving (you can scrap them off) and you can work with them for a period of time before they dry. Acrylic and watercolor need a basic understanding of color and values first, because every stroke is permanent. The same with pastels, all the mixing and layering is on the paper.

In art school I focused on oils, but I had to do some work in acrylic, watercolor and pastels. The idea being that you reinforce, and have better understanding, of what you know by trying different mediums. When I move from oils to pastels or watercolor it helps me see that the same aspects are important in both. It keeps me from getting too caught up in technique and think more about what's important; design, values, patterns and color temperature.